Opinion - The Sexuality of Vampires

The human condition is vast and multifaceted but few of those aspects are as important or as intense as sexuality. Like other creatures the human body inherently lives to reproduce but it is the ability to reason and feel genuine emotion that separates humanity from the animal kingdom. Over the course of art history, few creations have done more to bring to mind the raw animal nature of sex and the political and social implications of gender like the vampire. Complete with penetration, exchange of bodily fluids, and maturation, the vampire is the physical embodiment of sex: beautiful, powerful, dangerous. Although the focus of the genre has changed over the course of the last four centuries, the reflection of society’s views on sex and gender have always been present. The vampire is a continuously evolving embodiment of the ever-shifting focus on sexuality, sexual politics, gender roles, and their place in society.

The vampire has existed in mythology and folklore since before recorded history. Tales of beasts seducing and draining the blood of the living have been passed down orally for thousands of years, usually with references or connections to evil or, in Judeo-Christian cultures, Satan. Stephan Bolea states: “The vampire expresses the fear of the theologians, that transcending both good and evil is the work of a demon, the endeavor of an purely evil being. In Jungian terms, the vampire might be the personification of the shadow archetype, the sworn enemy of mankind, the tempter or the principle of evil incarnate (in other words a variation of the devil)” (Bolea 281). In literature, the first documented case of a vampire was in Heinrich August Ossenfelder’s 1748 poem “Der Vampire” which utilizes the first person narrative to tell the story of a vampire and his prey. As would be the case for subsequent vampire fiction, Ossenfelder uses sexual imagery to discuss the creature, having his narrator seduce a young virgin away from her mother’s teachings. The vampire is a symbolic representation of temptation, especially sexual temptation, and the ensuing freedom succumbing to such enticement would bring. Oseenfelder’s narrator speaks poetically about his mark, stating:

My dear young maiden clingeth

Unbending, fast and firm

To all the long-held teaching

Of a mother ever true. (Ossenfelder lns. 1-4)

Unbending, fast and firm

To all the long-held teaching

Of a mother ever true. (Ossenfelder lns. 1-4)

By awakening that sexual aspect of the young woman, she breaks bonds with the teachings of her family and her mother and becomes her own person. Women in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were supposed to be quiet, docile, pure, and subservient to their male counterparts and “thus the social superiority of man over woman embedded in metaphysical notions…and man was placed hierarchically above woman” (Hendershot 374). Women were viewed as objects and therefore, the vampire polluted this idea by soiling their purity, a symbolic reference to sex and sexual desire.

John Polidori’s 1819 short work “The Vampyre” also focuses on this aspect, detailing the life of a man named Aubrey and his consistent interactions with Lord Ruthven, who turns out to be the eponymous creature. Lord Ruthven uses his powers to seduce young, innocent women before killing them. Two women are killed by this vampire, the first a young Greek girl who catches Aubrey’s eye with her “innocence, so contrasted with all the affected virtues of the women among whom he had sought for his vision of romance” (Polidori). Aubrey’s sister is described in similar fashion as “only eighteen, and had not been presented to the world, it having been thought by her guardians more fit that her presentation should be delayed until her brother's return from the continent, when he might be her protector” (Polidori). Women such as these and the young maiden (virgin) in Ossenfelder’s poem, were perfect victims for the creatures who would seduce and then kill them. This social commentary reflects the idea that women who opened up sexually lost all value, a belief that has lasted until the present day. In these early vampire stories, once the creature seduces the innocent girl, she ceases to exist—she dies and is lost to the world.

This theme of seduction has maintained a place in the vampire genre spanning all centuries of its existence, even as the social commentary has shifted from female subservience to increasing female power in the world. Both seminal Vampire works of the eighteenth century, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla and Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, utilize the seduction of main characters to show the power of sexuality and its inherent poisonous effects on young women and their expected roles. Carmilla utilizes lesbianism to show the twisted and unholy aspect of sexual desire. The narrator at first repels the advances of her young companion but eventually gives in and becomes deathly ill. Even a father’s love could not restore the child’s purity as it had been tainted by sexual desire (the vampire) and the work ends with an implication of the approaching death of the narrator:

The following Spring my father took me a tour through Italy. We remained away for more than a year. It was long before the terror of recent events subsided; and to this hour the image of Carmilla returns to memory with ambiguous alternations--sometimes the playful, languid, beautiful girl; sometimes the writhing fiend I saw in the ruined church; and often from a reverie I have started, fancying I heard the light step of Carmilla at the drawing room door. (LeFanu 98)

This story implies yet again that sexual desire and awakening will tarnish the woman and, despite even the efforts of her loved ones, she will eventually be lost.

Dracula deals with the same dangers of sexuality but uses those to emphasize the growing role women were beginning to play at the turn of the century. This shift begins the next phase of vampire literature which focuses on the societal impacts of women who began to experience freedom of their own. The novel is rife with references to “the new woman,” a concept which refers to “women of affluence and sensitivity, who despite or perhaps because of their wealth exhibited an independent spirit and were accustomed to acting on their own. The term New Woman always referred to women who exercised control over their own lives be it personal, social, or economic” (Bordin 2). The character of Lucy in Dracula is rich and beautiful, a stereotypical aristocratic nineteenth century woman who receives multiple engagement offers and laughingly revels in her place as a future wife. She bases her worth on the desire men have for her, making her the perfect representation of what a woman should be. She tells her friend: “Here I am, who shall be twenty in September, and yet I never had a proposal till today, not a real proposal, and today I have had three. Just fancy! THREE proposals in one day! Isn’t it awful! I feel sorry, really and truly sorry, for two of the poor fellows. Oh, Mina, I am so happy that I don’t know what to do with myself” (Stoker 60). Her role has been fulfilled but that dream is soon dashed as the vampire seduces and transforms Lucy into a sexual monster. Instead of being reserved and observing propriety, she begins to attack her fiancé sexually and her manner changes until she is consumed by sexuality and her need to seduce:

She still advanced, however, and with languorous, voluptuous grace, said:-

“Come to me, Arthur. Leave these others and come to me. My arms are hungry for you. Come, and we can rest together. Come, my husband, come!”

There was something diabolically sweet in her tones—something of the tingling glass when struck—which rang through the brains of even us who heard the words addressed to another. As for Arthur, he seemed under a spell. (Stoker 227)

There was something diabolically sweet in her tones—something of the tingling glass when struck—which rang through the brains of even us who heard the words addressed to another. As for Arthur, he seemed under a spell. (Stoker 227)

Lucy becomes a monster because of her sexual awakening and her impurity is then a danger to the world. This commentary is meant as a warning to the dangers of a growing female power in society and its threat to the established patriarchy.

Stoker uses the same language throughout Dracula to talk of the dangers of sexuality, especially in women. Whenever women are strong and sexuality, they are described as languorous and voluptuous, usually in a dangerous context. Early in the novel, the protagonist is trapped in a room with women who sexually molest and assault him but he can do nothing because they have all the power. Dracula has three “brides” who use their sexual power to overtake the pure, resolute, Godly man:

The girl went on her knees, and bent over me, simply gloating. There was a deliberate, voluptuousness which was both thrilling and repulsive, and as she arched her neck she actually licked her lips like an animal…I could feel the soft, shivering touch of the lips on the super sensitive skin of my throat, and the hard dents of two sharp teeth, just touching pausing there. I closed my eyes in languorous ecstasy and waited—waited with beating heart. (Stoker 40-41)

The women are painted as uncontrollable savages, forcing men to do their bidding and utilizing their femininity to destroy him. Stoker goes so far as to have them eat the flesh of a living baby when they must stop their seduction, driving home the evil aspects of their sexuality. They also attempt to feminize the protagonist by penetrating him instead of vice versa, polluting and twisting sexual and social norms and creating an even more evil and subversive image: “Jonathan's encounter with the vampire women in the Castle Dracula further underscores the threat posed by the vampire body to traditional masculinity. His desire to be penetrated by the vampire women feminizes him as he waits ‘in a languorous ecstasy’ for the vampire bite” (Hendershot 381). In both the workplace and society in general, the growing female presence began to threaten the status quo and the vampire became a symbolic representation of increasing female autonomy, both social and sexual.

Another famous work, 1954’s I am Legend, saw one of the first in a blending of genres—vampires and zombies. Richard Matheson, the author, created a world in which there was a worldwide apocalypse and only one man, Robert Neville, survived. He is continuously tempted by vampires outside of his door to come out, using sexual calls and acts to try and draw him out: “He never looked at them anymore. In the beginning he’d made a peephole in the front window and watched them. But then the women had seen him and had started striking vile postures in order to entice hum out of the house” (Matheson 7). It isn’t until later that Neville understands this new society and that they are just as afraid of him as he is of them. The women use their sexuality as a defense mechanism, a way to lure out their fear and destroy it, representing the shifting ways in which women had to adjust to their surroundings in order to establish their roles in society.

As the twentieth century continued, the vampire genre evolved yet again to reflect societal shifts. Instead of focusing on the fear of women and their growing roles in society, vampires began to embody a younger role, embracing sexuality and becoming romantic and erotic characters. Andrew Schopp states that “although it has long held a formidable place in the heart of western culture, until the nineteenth century the vampire existed primarily as a creature to be feared, the revenant come back to torment the living…however, the vampire transformed from a feared cultural phenomenon to a desired cultural product, from mythic explanation of the unknown to receptacle of cultural desires” (Schopp 231). Aside from two-dimensional horror tropes utilized in the Hammer films of the sixties and seventies, vampires began to take on a new role as romantic, misunderstood beings who pine for belonging in a world that would never accept them.

Few writers have done more genre-defining work than Anne Rice and her Vampire Chronicles. Through her work, she created characters who were from the outside, not truly accepted by their own world and so they walk alone. Rice’s characters are fluid within their own sexuality, whether it is hetero or homosexual and those blurred lines are indicative of the shifting society in the seventies.

Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles might constitute the most developed treatment of the homoerotic/homosocial. Rice’s novel’s contain a plethora of male-male couples…the popularity of Rice’s books is stunning, especially since they offer such detailed erotic relations between men. The reason behind their popularity may rest in the fact that, since the vampire world enables the creation of alternatives, the reader can feel safe enjoying the alternative male/male relations. (Schopp 238)

Louis de Pointe du Lac, the protagonist of Rice’s first novel, Interview with the Vampire, becomes a creature of the night and exists for centuries on the fringes of society, constantly mourning his loss and his humanity, afraid of who he truly is. His struggle is indicative of the fight for self-realization in homosexuals who feel they don’t belong. Louis’ life is too hard and it takes him coming to terms with what he is to understand who he is and embrace his lot in life—his vampirism: “I wanted love and goodness in this which is living death,' I said. `It was impossible from the beginning, because you cannot have love and goodness when you do what you know to be evil, what you know to be wrong. You can only have the desperate confusion and longing and the chasing of phantom goodness in its human form” (Rice 360). Rice creates an existence full of heartbreak and emotional intensity for her character to navigate because, like real life, is world was messy. Her use of homosexual imagery, later well-enforced in the 1994 adaptation of the novel, was a great look into the way society viewed the gay community.

Vampire films of the twentieth century were an amalgam of serious drama, social commentary, and eroticism, reflecting the shifting spotlight and societal acceptance of sexuality in the public eye. 1983’s same-name film adaptation of Whitley Strieber’s novel The Hunger, much like Rice’s work, deals with the subject of open sexuality. The main character Miriam, portrayed by Catherine Deneuve, takes on lovers from both sexes to ease her loneliness because her partners never survive as long as she does. The movie, painted as much more erotic than the novel, pays special attention to the sex scenes, creating a vampire tale based almost entirely on the erotic. As society evolved and sexuality became less of a taboo, sexually exploitative vampire films can be seen time and again, through low-budget, sex-based movies. The sixties and seventies contained multiple films which exploited sexuality through vampires, focusing on lesbianism to build the erotic: 1960’s Blood and Roses (an erotic adaptation of Carmilla), 1970’s The Vampire Lovers, 1971’s Requiem for a Vampire, Daughters of Darkness, and Countess Dracula, 1972’s The Blood Splattered Bride, 1974’s highly censored Vampyres, and 1975’s Mary, Mary, Bloody Mary and The Female Vampire. This trend came into the mainstream in the Alyssa Milano cult classic, 1995’s Embrace of the Vampire. The lesbian sex scenes were amped up and became the ultimate selling point of the film: “This change was part of an era when movies were liberated from restriction of sexual content and the encouragement of sexuality. The larger context of liberation from censorship should not obscure the fact that from then on we went to vampire movies in particular, not to be frightened but to be turned on” (Beck 91). Alternative sexuality had taken hold of American society in the second half of the twentieth century and this was reflected in the shift of vampire portrayals in film.

In eighties also saw a rise in the teen and young adult driven vampire films focused on characters of the same age. 1985’s Fright Night deals with a group of friends who attempt to expose and eventually destroy a powerful vampire who has moved in next store. The film reflected the style and substance of the eighties, complete with soundtrack and slang, and even embraced classic tropes such as the virginal young woman being seduced. That role was reversed in both The Lost Boys and Near Dark which featured a male protagonist being seduced and eventually turned by a female threat. The growing societal belief in the sexual prowess of women can be seen in these movies which show women who are unafraid of their sexuality, even if they are afraid of the vampirism itself. The women are actually the stronger of the characters until the climax of the film in which the men finally arrive at the same level of power. These movies began a new subgenre of vampire film, the vampire coming-of-age story, which showcases someone dealing with growing up, but with the backdrop of a vampire story. In Fright Night, The Lost Boys, and Near Dark, the protagonists don’t feel secure or sure of themselves but by going through their struggle with vampires, which represent both the dangers of life and the growing sexuality inherent in puberty, they grow to become self-assured and confident in their roles.

This pattern can be seen across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries where the vampire has become the hero, the misunderstood character who just wants to be loved, and who has so much to offer the world. In the 1998 film Blade, the audience is presented with an interracial character, half vampire, half human, who is somewhat spurned by both parties. This representation of interracial relationships and, in essence, mixed-race children, adds another aspect to vampire sexual lore. Blade cannot fully join the human race but is blackballed by vampires as well, causing him to feel outside society. It is only in his purpose as a hunter that he has found solace, an idea which can be seen in other vampire works such as 1985’s Vampire Hunter D, which follows roughly the same storyline. In dramas such as these, the sexuality happens before the film and results in the current predicaments of the protagonists.

The combination of multiple genres focused on a vampire-laden world and character list was fully realized in 1992’s film Buffy the Vampire Slayer and 1997’s series of the same name. The series was landmark in multiple ways, one being its female protagonist who never truly needed to be saved. Beck states:

A milestone in this new path was the appearance in 1992 of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Rosenman, Kuzui, & Kuzui, 1992), an unlikely vampire movie aimed at teen audiences with a female protagonist. This heroine was also fashioned to include elements of satire. [This] movie not only created a novel pattern for [its] main character, [it] also appropriated the admirable traits of standard male heroes for [its] previously marginalized girl protagonist. (Beck 91)

For almost all instances in the series, it was Buffy’s own innate abilities that defeated the powers of darkness, causing the show to become a beacon for female empowerment. Series creator Joss Whedon:

For almost all instances in the series, it was Buffy’s own innate abilities that defeated the powers of darkness, causing the show to become a beacon for female empowerment. Series creator Joss Whedon:

…situates Buffy within contexts mirroring the realities faced by many American girls and women. When walking alone in public at night, Buffy is threatened with the violence many fear, namely being followed by an unknown man, ending up trapped in dark alley with him, and becoming a rape and/or murder victim. But rather than becoming a victim, Buffy is the hero. She is not only capable of effective self-defense, but week after week, Buffy seeks out danger in an attempt to eradicate threats of violence toward others. (Jackson 42)

The series combined serious drama, teenage hijinks, comedy, and romance, giving the world one of the most well-known relationships between a vampire and human: Angel and Buffy. Their relationship was complicated and when he eventually turned evil, the show became serious, attacking the ideas of abusive relationships and sexual violence. Buffy the Vampire Slayer reflected multiple aspects of the society from whence it grew and the show evolved with the times, also introducing one of the first openly gay couples on television. Buffy in essence utilized the idea of the coming of age, with “the show’s specific preoccupation with youth and with growing up…but the question of what it is like to go through the process of ‘becoming sexual’ and securing intimacy, in the circumstances young people now encounter” (135) cannot be overlooked. Not only did the series provide a mirror for society but it also shed light on the problems of youth during its run, and handled those sexual and maturation concepts with a serious approach.

The need for belonging and sexual understanding is incredibly important in John Adjvide Lindquist’s acclaimed 2004 novel Let the Right One In. This novel details the coming of age of a young boy who is bullied mercilessly at school, ignored by every adult who should be helping him, and who suffers from sociopathic tendencies. He meets a young girl who helps him realize how strong and important he truly is. The novel is a drama and, although it does include vampires, focuses on the aspect of sexual maturation and sexual identity. The girl, Eli, is in fact a prepubescent, castrated boy who must live as a girl in order to survive in the world. Oskar, the boy, doesn’t mind and there are exchanges between the two young characters which discuss sexuality in a somewhat open manner:

“Oskar, do you like me?”

“Yes. A lot.”

“If I turned out not to be a girl…would you still like me?”

“Yes…I guess so.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.” (Lindquist 125)

“Yes. A lot.”

“If I turned out not to be a girl…would you still like me?”

“Yes…I guess so.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.” (Lindquist 125)

On par with growing acceptance of homosexuality in children, Lindquist has crafted characters who do not care about what society thinks but instead simply want to feel loved. The book is rife with sexuality, most of it negative and violent. Eli is cared for by an ageing pedophile because it is the only way he can survive.

Simon Bacon states that because of this relationship, “the monstrosity of the vampire is linked to the monstrosity of that relationship,” (Bacon 28), a social commentary on the ways in which children with alternative sexualities are cared for and often abused but refuse to seek help because there is still a strong social taboo against the subject.

Simon Bacon states that because of this relationship, “the monstrosity of the vampire is linked to the monstrosity of that relationship,” (Bacon 28), a social commentary on the ways in which children with alternative sexualities are cared for and often abused but refuse to seek help because there is still a strong social taboo against the subject.

The twenty-first century has also seen the latest and arguably most powerful transformation of the vampire genre. Teen romance has become a common theme and the focus of a large number of works, both literature and film, is on paranormal romance and According to statistics brought out by Romance Writers of America, in 2009, the paranormal subgenre made up 17.16% of the popular romance genre” (Bailie 141).

The vampires in these stories have shed their Satanic or evil qualities and instead are seen as heroes. They suffer because they are good and want to live a better life, and,

The vampires in these stories have shed their Satanic or evil qualities and instead are seen as heroes. They suffer because they are good and want to live a better life, and,

Depictions of the modern vampire, as opposed to the older traditional vampires modeled on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, have ‘‘very little of that metaphysical, anti-Christian dimension . . . his . . .evil acts [being] expressions of individual personality and conditions, not of any cosmic conflict between God and Satan’’ (18). In these romances it is this that demarcates the vampire hero from the vampire as villain; the evil vampire makes a deliberate choice to embrace his darker nature, while the vampire hero not only struggles against the temptation but will sacrifice himself rather than succumb to it. (Bailie 143)

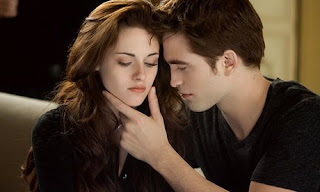

The Twilight Saga, spanning five films adapted from four Stephanie Meyers novels, have become a world-wide phenomenon. The main vampires in Meyer’s works do not kill humans but survive on animal blood. The main character, Bella, a young woman, is seemingly ordinary but falls madly in love with Edward, a vampire. The books and films themselves pay little attention to the actual sexuality except to say that both characters want to have intercourse but refrain from doing so until they are wed and, in a stunning departure from classic tropes, it is the female who is trying to have sex and the male who is forcing restraint.

“No,” he promised solemnly. “I swear to you, we will try. After you marry me.”

I shook my head, and laughed glumly. “You make me feel like a villain in a melodrama — twirling my mustache while I try to steal some poor girl’s virtue.”

His eyes were wary as they flashed across my face, then he quickly ducked down to press his lips against my collarbone.

“That’s it, isn’t it?” The short laugh that escaped me was more shocked than amused. “You’re trying to protect your virtue!” I covered my mouth with my hand to muffle the giggle that followed. The words were so . . . old-fashioned.

“No, silly girl,” he muttered against my shoulder. “I’m trying to protect yours. And you’re making it shockingly difficult.” (Meyer 262)

I shook my head, and laughed glumly. “You make me feel like a villain in a melodrama — twirling my mustache while I try to steal some poor girl’s virtue.”

His eyes were wary as they flashed across my face, then he quickly ducked down to press his lips against my collarbone.

“That’s it, isn’t it?” The short laugh that escaped me was more shocked than amused. “You’re trying to protect your virtue!” I covered my mouth with my hand to muffle the giggle that followed. The words were so . . . old-fashioned.

“No, silly girl,” he muttered against my shoulder. “I’m trying to protect yours. And you’re making it shockingly difficult.” (Meyer 262)

The series is full of monogamy and celibacy, reflecting the newer, younger audiences who have become fanatics of the series. The two lovers don’t have sex until they are married and, although the passion is palpable, they refrain out of decency. The books and films represent Meyer’s own devout Mormon beliefs.

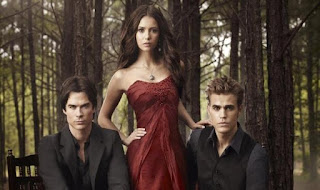

Twilight’s success caused a large influx in more series which were similar in scope. Although the books for The Vampire Diaries began long before Twilight, Meyer’s success caused a resurgence and explosive effect and L.J. Smith’s works were revisited by millions of fans, warranting a highly successful television series of the same name. The Vampire Diaries television series, while maintaining many of the same tropes as Twilight, is much more sexual and far darker than its predecessor. This teen-romance television show is far more realistic at representing the current state of teenage sexuality and the danger that many conservative people feel is inherent in sex. Teresa A. Goddu says that “the teenage vampire serves as a threatening image of family values gone awry—the child as soulless killer, as homegrown horror” (qtd. in Heidenreich 92). The passion and emotion exhibited by the characters screams teenage melodrama. In works such as The Vampire Diaries and similar fare, the couple isn’t just after sex or love but a complete acceptance of each other, something that in a culture like America, is strived for constantly within the younger generation. Bailie states that “For the couple, the ultimate fulfillment of desire in the paranormal romance is not only sexual but, more importantly, since through the blood exchange nothing is concealed from the other, the knowledge that they unreservedly embrace the other’s true nature” (Bailie 147).

Yet another series which began before Twilight but garnered a television show after its success was Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse Series which was turned into True Blood. This series is a mix of the emotion and passion of The Vampire Diaries with the sexuality of twentieth century exploitation films. The sex is heavy and often and oftentimes the story struggles because of it but it is another representation of how society views sexuality. There is a social commentary about interracial sexual relationships through the course of the series. Vampires live in the open with humans and, like interracial relationships in society, are viewed with disdain by many. The statement is obvious and enforced well and there are wonderful representations of all types and races: black, white, Spanish, gay, straight, bisexual, etc. Tia Sheree Gaynor states that “the racism (that is to say, naturalism), prejudice, segregation, violence, and intolerance so boldly presented in True Blood are highlighted by the narratives against integration. The discourse is eerily similar, seemingly purposely on the creator’s part, to historic and contemporary narratives in American society” (Gaynor 359). True Blood is the perfect representation of sexual diversity, racism, struggle, and acceptance in modern society.

Although genre is always evolving, the vampire genre is inherently focused on the same basic themes: sexuality and acceptance of others and self. Margot Adler states that “vampires simply reflect the fears and concerns of any age. And today's vampires, from the Cullens in "Twilight" to Angel and Spike in "Buffy," are struggling to be moral despite being predators” (Adler 6). Whether the creature is a monster, a sexual being, a child, or just simply misunderstood, they are reflections of all aspects of society and “they must adapt themselves to the always-changing culture and customs of human existence” (Schopp 234). Through the use of the vampire creature, authors and filmmakers have been able to establish social commentary which is relevant to this day and which changes as is needed to continuously reflect society and its shifts.

Works Cited

Adler, Morgot. “Heart of Darkness.” Nieman Reports 68.2 (2014): 6. Print.

Bacon, Simon. “The Right One or the Wrong One?: Configurations of Child Sexuality in the Cinematic Vampire.” Red Feather Journal 3.1 (2012): 24-36. Print.

Bailie, Helen T. “Blood Ties: The Vampire Lover in the Popular Romance.” The Journal of American Culture 34.2 (2011): 131-48. Web.

Bolea, Stefan. “The Shadow Archetype of the Vampire in Three Horror Movies.” Media Mythologies 28 (2015): 281-89. Print.

Beck, Bernard. “Fearless Vampire Kissers: Bloodsuckers We Love in Twilight, True Blood, and Others.” Multicultural Perspectives 13.2 (2011). 90-92. Web.

Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson. Alice Freeman Palmer: The Evolution of a New Woman. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 1993. Print.

Gaynor, Tia Sheree. “Vampires Suck: Parallel Narratives in the Marginalization of the Other.” American Theory & Praxis 36.3 (2014): 348-72. Print.

Heidenreich, Linda. “Vampires Among Us.” Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 24 (2012): 92-101. Print.

Hendershot, Cyndy. “Vampire and Replicant: The One-Sex Body in a Two-Sex World.” Science-Fiction Studies 22 (1995): 373-398). Print.

Jackson, Debra. “Throwing Like a Slayer: A Phenomenology of Gender Hybridity and Female Resilience in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Slayage: The Journal of Whedon Studies 14.1 (2016): 41-70. Print.

LeFanu, Joseph Sheridan and James Ridenhour. Carmilla. Richmond: Valencourt, 2009. Print.

Lindquist, John Adjvide. Let the Right One In. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin/Thomas Dunne, 2008. Print.

Matheson, Richard. I am Legend. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 2007. Print.

Meyer, Stephanie. Eclipse. New York: Little, Brown, 2007. Print.

Ossenfelder, Heinrich August. “Der Vampire.” Firbolg Publishing. Wordpress. Web. 9 August 2016.

Polidori, John. “The Vampyre.” Project Gutenberg. Web. 9 August 2016.

Rice, Anne. The Vampire Chronicles. New York: Ballantine, 1993. Print.

Richards, Chris. “What Are We? Adolescence, Sex, and Intimacy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 18.1 (2004): 121-37. Print.

Schopp, Andrew. “Cruising the Alternatives: Homoeroticism and the Contemporary Vampire.” The Journal of Popular Culture 30.4 (1997): 231-43. Web.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. New York: Bantam, 2004. Print.

Bacon, Simon. “The Right One or the Wrong One?: Configurations of Child Sexuality in the Cinematic Vampire.” Red Feather Journal 3.1 (2012): 24-36. Print.

Bailie, Helen T. “Blood Ties: The Vampire Lover in the Popular Romance.” The Journal of American Culture 34.2 (2011): 131-48. Web.

Bolea, Stefan. “The Shadow Archetype of the Vampire in Three Horror Movies.” Media Mythologies 28 (2015): 281-89. Print.

Beck, Bernard. “Fearless Vampire Kissers: Bloodsuckers We Love in Twilight, True Blood, and Others.” Multicultural Perspectives 13.2 (2011). 90-92. Web.

Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson. Alice Freeman Palmer: The Evolution of a New Woman. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan, 1993. Print.

Gaynor, Tia Sheree. “Vampires Suck: Parallel Narratives in the Marginalization of the Other.” American Theory & Praxis 36.3 (2014): 348-72. Print.

Heidenreich, Linda. “Vampires Among Us.” Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 24 (2012): 92-101. Print.

Hendershot, Cyndy. “Vampire and Replicant: The One-Sex Body in a Two-Sex World.” Science-Fiction Studies 22 (1995): 373-398). Print.

Jackson, Debra. “Throwing Like a Slayer: A Phenomenology of Gender Hybridity and Female Resilience in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Slayage: The Journal of Whedon Studies 14.1 (2016): 41-70. Print.

LeFanu, Joseph Sheridan and James Ridenhour. Carmilla. Richmond: Valencourt, 2009. Print.

Lindquist, John Adjvide. Let the Right One In. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin/Thomas Dunne, 2008. Print.

Matheson, Richard. I am Legend. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 2007. Print.

Meyer, Stephanie. Eclipse. New York: Little, Brown, 2007. Print.

Ossenfelder, Heinrich August. “Der Vampire.” Firbolg Publishing. Wordpress. Web. 9 August 2016.

Polidori, John. “The Vampyre.” Project Gutenberg. Web. 9 August 2016.

Rice, Anne. The Vampire Chronicles. New York: Ballantine, 1993. Print.

Richards, Chris. “What Are We? Adolescence, Sex, and Intimacy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 18.1 (2004): 121-37. Print.

Schopp, Andrew. “Cruising the Alternatives: Homoeroticism and the Contemporary Vampire.” The Journal of Popular Culture 30.4 (1997): 231-43. Web.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. New York: Bantam, 2004. Print.

Image - Wikipedia/Amazon/Imdb.

Post a Comment